Imagination, Dramatic Play, and Critical Thinking

A Case for Imagination

Sometimes, the simplest question is this- “What is the point?” What is the point in engaging in imagination, imaginative play, or reading fantasy? Critics of fantasy, children’s literature, and other speculative media are often against the genre because they aren’t “serious” enough or too escapist. However, one could argue that fantasy peels back the layers of reality and provides a new lens for us to analyze, critique, and make changes in our primary world. As a teacher, I can teach my students how to read and write like a literary critic, but I also want my students to develop their imagination, particularly in an age where visual media, social media, and artificial intelligence can limit that development. How do I teach students who struggle to create pictures in their minds, to visualize possibilities, and infer ideas?

To answer these questions, I’ll start with my experiences with early literacy development and the elementary ages, at the roots of the mountain (so to speak).

Once upon a time, I taught in an early childhood literacy center. In addition to our little classrooms and cozy reading nooks, we also had a dedicated space for dramatic play. The students could dress up, manipulate a play kitchen, and “grow” flowers. Many parents would ask me, “What is Dramatic Play, and why is it necessary in preschool programs?” “Why does my son’s classroom have such elaborate play centers?” “Why does it matter?” In terms of literacy… it can matter quite a lot!

Firstly, Dramatic Play is a set space and time in which teachers allow for activities that include dress up, play sets that mimic life experiences, and guided prompts from teachers. In Dramatic Play, the children are strengthening their oral language skills and social development through play, and teachers act as guides for students to use their imaginations to solve puzzles, create language, and determine the social nuances needed for the situation.

Excell and Linington (2011) assert that play activities are crucial in developing the implicit pathways to literacy that are present in perceptual-motor skills1 ( and sensorimotor integration2 They cite the use of well planned, good quality play (Wood, 2009) to stimulate and link the neural pathways between these motor skills and literacy development. A pedagogy of play must include not only free play and spontaneous movement activities, but also structured, purposeful guided movement experiences designed to support specific aspects of gross motor, fine motor, and perceptual motor development, which thus lends itself to early literacy development (2011). The benefit of a pedagogy of play is that it is flexible, and that teachers are expected to link these movement-based activities with multiple literacy facets, such as oral language, communication, and critical thinking skills. A pedagogy of play and movement can help students strengthen, for example, the link between visual and auditory memory (being able to remember what is seen or heard) and the link between a letter and its sounds (Excell & Linington, 2011).

With Dramatic Play, students not only have fun dressing up and playing with toy sets, but they are also learning how to manipulate the toys based on norms set by the teacher, and by previous experiences they’ve witnessed at home. For example, with a kitchen set, students know that they have to turn on the “oven” in order to cook the food. In most cases, the students have witnessed their guardian cooking, or the teacher has given them the instruction to turn on the oven and cook. With guided instruction, students learn how to manipulate tools and social situations through these Dramatic Play sessions. Teachers should also use oral instruction and important vocabulary during these play sessions so that the students’ oral development skills are growing, and they are learning to associate certain vocabulary words with specific situations. For more instruction on integrating vocabulary in oral instruction, view this video here.

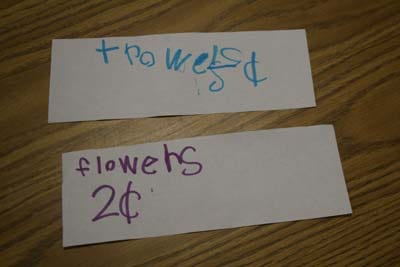

Many teachers take the opportunity to integrate literacy skills in Dramatic Play by giving the students a task to complete, and then creating literacy cards or worksheets that supplement the task. For example, when creating a Flower Shop, this teacher integrated math and literacy by providing different baskets with flowers, flowerpots, seeds, and a set space to plant a “garden,” complete with a cash register and receipts. Not only does this Dramatic Play sequence integrate math, but it also requires them to handwrite the final product for the recipient, and it puts the students in the roles of consumer and shop owner so that they can learn the social interactions that come with shopping. Providing clipboards, sticky pads, or forms (real or created) enhances the natural connection between play and the written word (Writing in the Dramatic Play Center).

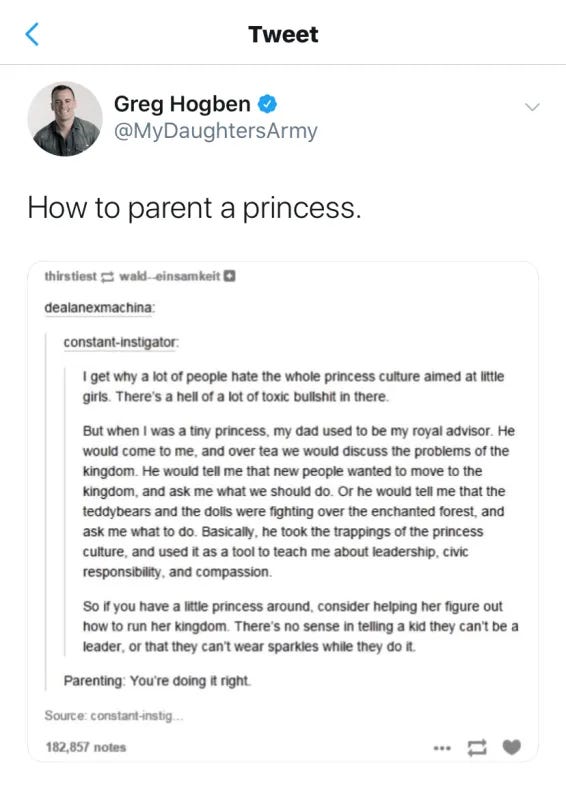

Parents and homeschool teachers can benefit easily from engaging in structured Dramatic Play with their children. Giving your children ample opportunities to dress up and integrate literacy and writing in everyday situations helps prepare students not only for reading and writing in the long run, but also for their social-emotional development and their attention to understanding the world around them. Dramatic Play is a beneficial opportunity to teach students about social situations that may be complicated or uncomfortable, and to act out possible solutions to problems. For example, Greg Hogben @MyDaughtersArmy retweeted a post on Tumblr several years ago that had many parents singing praises.

The parent in question had taken an overused and uncomfortable trope and transformed it through the use of excellent and guided dramatic play. This father knew that there was more to being a princess than simply dressing up in cute outfits, and he took the opportunity to use his daughter’s love for princesses and tea parties to teach her how to be a leader, a negotiator, and a strategist. This is the magic of Dramatic Play- using your imagination and theirs to counter, question, and to develop critical thinking through the magic of pretend.

Two key literacy skills include the ability to visualize or creatively infer possibilities that aren’t blatantly present in a text. This creative level of thinking can be hard for young children and for those who might think in literal terms. I remember working with a four year old who struggled to use their imagination in my class because they* had little to no exposure to imaginative thinking. Their parents completely forbade screens in the home (which is another conversation entirely), and there appeared to be very little dramatic or imaginative play when they interacted with each other.** As a result, my student often stayed strictly in their comfort zone. They were interested in subjects that are “true,” and they would smugly tell me me when “that’s not true” or “that’s not real.” To my understanding, they read very few imaginative fiction books at home, except for the occasional Dr. Seuss. Fairy tales and fantasy were a complete mystery to them. If I posed predictive questions about the text (“What do you think is going to happen next?”), their automatic answer was “I don’t know.” When they retold the story we read together in a Story Map, they were more comfortable drawing things realistically, and would refuse to draw at all if I asked them to “use [their] imagination.”

What, then, are the consequences for this student? What happens when imagination or creative thinking is limited or undernourished? A study by M. Root-Bernstein and R. Root-Bernstein (2006) posits that imaginative world-building in early childhood contributes to creative thinking in adults. While previous research declared early imaginative play to be “uncommon and associated with the arts,” the data in Root-Bernstein and Root-Bernstein’s study “validated [their] expectation that individuals inventing imaginary worlds in childhood participate as adults in a wide variety of disciplines,” including scientists, artists, and those who work in the social sciences and humanities.

Particularly in the social sciences and sciences, creative (older) individuals were significantly more likely to have engaged in childhood worldplay than students anticipating careers in these fields. In addition, over one half of the study’s select and general populations recognized an important role for worldplay in their adult vocations and avocations. … the invention of imaginary worlds is not some obscure form of make-believe, but rather a phenomenon of wider cognitive import. …

Finally, we argue that worldplay at any age and in many guises presents a microcosm with which to explore the complex nature of creativity itself. Mature worldplay at work, in particular, may add a nuanced perspective to the ongoing discussion of creative individuals as generalists or as specialists. Creativity is such that an individual must combine previously disparate elements of knowledge and action into something novel and effective.

M. Root-Bernstein and R. Root-Bernstein, (2006) “Imaginary Worldplay in Childhood and Maturity and Its Impact on Adult Creativity.”

This research ultimately shows that imaginative play and world building is essential for children and adults to succeed in consequential for the child, it is also consequential for the adult. When children and adults engage in imaginative and creative thinking, they can embrace problems with many different possibilities. Entrepreneurs, scientists, and artists all need imagination in order to thrive and grow in their respective vocations, just as a child needs imagination and play to be happy in their day to day experiences.

References

Excell, L., & Linington, V. (2011). Move to literacy: Fanning emergent literacy in early childhood education in a pedagogy of play. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 1(2), 27-45.

Cooper, Sheryl. (2018, June 9) 25+ Dramatic Play Activities for Toddlers and Preschoolers. Teaching2and3yearolds. https://teaching2and3yearolds.com/dramatic-play-activities-for-toddlers-and-preschoolers/

Pre-K. Pages. Dramatic Play: Archive. Pre-Kpages.com. https://www.pre-kpages.com/category/dramatic-play/

Root-Bernstein, M., & Root-Bernstein, R. (2006). Imaginary Worldplay in Childhood and Maturity and Its Impact on Adult Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 18(4), 405–425. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1804_1

Wood

Perceptual motor skills: a child’s developing ability to interact with his environment by combining the use of the senses and motor skills.

Sensorimotor integration: the capability of the central nervous system to integrate different sources of stimuli and to transform such inputs into motor actions.